I have to admit, this week for Saturday Night Genealogy Fun, Randy Seaver has come up with a truly unusual challenge.

Your mission this week, should you decide to accept it, is:

(1) Find some of your favorite sayings, aphorisms, jokes, etc. They can be genealogy-related, or not.

(2) Translate them into Latin using Google Translate (https://translate.google.com/?hl=en&tab=TT).

(3) Share them with us in your own blog post, in a comment to this post, or in a Facebook status line or Google+ stream post (impress your nongenealogy friends with your Latin skills!).

(4) Of course, you could translate the Latin you read (on my blog or the blogs of others) back into English (or your native language) using Google Translate too, to see who was really funny, or mean, or romantic. If you want to be really fancy, you could translate your sayings into any other language using Google Translate and really confuse all of us.

I'm going to start by admitting that with all the languages I know, whether well or at a more basic level, Latin is not one of them. I have managed to studiously avoid it all of these years. So whatever Google Translate gives me is what I'm going to post. I don't know how to clean it up.

That said, these are some of my genealogy truisms:

• Loquere ad seniorem domus membra primum.

• Numquam sperare in indicem ad in viscus.

• Quod si vos non petere, quod non statim responsum est.

• Fideliter cibi de jigsaw sollicitat similis investigationis.

• Conatus a singulis singula exemplum scriptum est potestis familia membra.

Somehow I doubt I will be impressing anyone with my Latin skills. And this exercise will definitely point out the dangers of relying strictly on machine translation to do your work for you.

Addendum, Tuesday, May 3, 2017:

These are the original sayings in English that I translated into Latin using Google Translate:

• Talk to older family members first.

• Never rely on only the index entry.

• If you don't ask, the answer is always no.

• Genealogy research is like a jigsaw puzzle. (Like it says at the top of my blog.)

• I accidentally deleted my original phrases, but this was something close to "I try to get copies of all records for family members." Unfortunately, I can't recreate the same translation!

Genealogy is like a jigsaw puzzle, but you don't have the box top, so you don't know what the picture is supposed to look like. As you start putting the puzzle together, you realize some pieces are missing, and eventually you figure out that some of the pieces you started with don't actually belong to this puzzle. I'll help you discover the right pieces for your puzzle and assemble them into a picture of your family.

Saturday, April 29, 2017

Thursday, April 27, 2017

Treasure Chest Thursday: General "Informations" Concerning the Estate of John Schafer

This is the "cover page" for a grouping of three pieces of paper. It is 8" x 9 7/8" and a yellowish off-white. This cover page is the back of page 3 (see below) and is a fairly heavy weight, more similar to a cover stock than a letter. The sheet has a watermark: "Symphony Lawn" in a script font. It was folded in thirds, and the fold lines are visible in the scanned image.

Pages 1 and 2 are also 8" x 9 7/8" and yellowish off-white. They are lighter in weight, have no watermark, have lines running horizontally across, and are of moderate quality. The three sheets are attached to each other by some sort of glue or paste in the upper left corner. The images of pages 2 and 3 show a diagonal line in the upper left where I folded the preceding page(s) over to make the scans. Everything on these pages is typed with the exception of a few items on page 2, which appear to be in Jean La Forêt's handwriting.

I found it interesting that Charles Frederick Schaefer was called "the moving spirit in all the transactions" on the cover. His name first appeared last July, on the page that had the names, addresses, and spouses of Emma's three half-siblings. He was Louisa's husband.

As I wrote above, almost everything here is typed, and it's easy to read. The only handwritten items are on page 2, in the section that starts with "DEDUCTION." For clarity, the lines with writing are:

What he bought for................ " 4475.00 4475–

Benefit..........$.– 6475.00 6475

Made out of transactions a Net benefice..of........$.18475.00 18475

The documents are written from Emma's point of view: "Brother August", "sister Alvina", "my sisters and brother", "my father's Property." That said, I'm not sure if she actually typed them or if Jean did. Based on the papers I've looked at, this seems more his style than hers, and "informations" is something I've seen before from a native French speaker writing in English. Maybe Emma dictated it to him.

The document begins with a nice timeline of various events from John, Elizabeth, and Emma Schafer's lives. One date not included is the actual day that John Schafer died, but it was no later than September 3, 1867, which is when Elizabeth was granted papers of administration to handle his estate. It took two and a half years to settle his estate, so it apparently was not totally straightforward.

The next few dates in the timeline agree with documents I've posted previously: Elizabeth Schafer did marry Louis Curdt, who was a widower, on January 22, 1874. Emma Schafer did marry Emile Petit on November 10, 1883. I don't seem to have a copy of the document that Emile and Emma signed when they sold Emma's interest in her father's estate, but on July 19, 1885 Louis Curdt signed a waiver attesting to that, so the date of July 9 sounds reasonable. Now I have a date for Elizabeth's divorce from Louis Curdt. It's interesting to see that the deeds for the land John Schafer had bought were back in Elizabeth's name right after the divorce.

Then we get into the sales and purchases of the land that was in John Schafer's estate. I have to admit, I'm confused by all the back and forth that occurred. I suspect I will need to plat all this out to figure out what happened. But it does appear at first glance that the Curdt siblings bought a lot of land from their mother at fairly low prices and then turned around and sold a lot of that land for much higher prices. So it seems that Emma was not the only person shortchanged in this series of transactions. Maybe Elizabeth understood what was going on, maybe she didn't. It certainly doesn't cast the Curdt children in the best light.

The Midland Golf Club referred to here must be the same one that Jean mentioned in last week's document. I'm not sure how the acreage in these pages correlates with the measurements from the previous one. Perhaps platting will help clear that up also.

As for the accusation that Charles Frederick Schaefer benefited the most — well, it's hard to argue that conclusion based on the information on these pages, but I don't know if this is all the information or if it has been presented fairly. Obviously something else I will need to look into after I've processed all of the documents I do have. I don't know how easily I'll be able to check on whether Schaefer really bought "automobiles and other commodities to his heart's desire" or "soak[ed] himself with whiskey", but it should be interesting to try.

And I'm still wondering whether Charles Frederick Schaefer was related to John Schafer, and whether Louisa married a (perhaps distant) cousin of her half-sister.

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

Sunday, April 23, 2017

Yom HaShoah: Remembering My Family Members

Yom HaShoah is the annual day of commemoration to honor and remember the Jewish victims of the Holocaust during World War II. It is usually held on the 27th of Nisan, which this year falls on April 23.

The following is the list of my known family members who died in the Holocaust. May their memory be for a blessing.

Beile Dubiner

Eliezer Dubiner

Herschel Dubiner

Moishe Dubiner

Sore Meckler Dubiner

Esther Golubchik

Fagel Golubchik

Lazar Golubchik

Peshe Mekler Golubchik

Pinchus Golubchik

Yechail Golubchik

Mirka Nowicki Krimelewicz

— Krimelewicz

Beile Szocherman

Chanania Szocherman

Maishe Elie Szocherman

Perel Szocherman

Raizl Perlmutter Szocherman

Zlate Szocherman

The following is the list of my known family members who died in the Holocaust. May their memory be for a blessing.

| Miami Holocaust Memorial, panel #26, Szocherman family names (March 2016)

Thank you to Barbara Zilber for the photograph. |

Beile Dubiner

Eliezer Dubiner

Herschel Dubiner

Moishe Dubiner

Sore Meckler Dubiner

Esther Golubchik

Fagel Golubchik

Lazar Golubchik

Peshe Mekler Golubchik

Pinchus Golubchik

Yechail Golubchik

Mirka Nowicki Krimelewicz

— Krimelewicz

Beile Szocherman

Chanania Szocherman

Maishe Elie Szocherman

Perel Szocherman

Raizl Perlmutter Szocherman

Zlate Szocherman

Saturday, April 22, 2017

Saturday Night Genealogy Fun: How Many Trees in Your Database?

One way to learn more about the capabilities (or lack thereof) of your family tree program is to take Randy Seaver up on his Saturday Night Genealogy Fun challenges:

Your mission this week, should you decide to accept it, is:

(1) How many different "trees" do you have in your genealogy management program (e.g., RootsMagic, Family Tree Maker, Reunion) or online tree (e.g., Ancestry Member Tree, MyHeritage tree)?

(2) How many trees do you have, and how big is your biggest tree? Do you have some smaller "bushes" or "twigs?"

(3) Tell us in your own blog post (please leave a link in Comments here), in a comment to this post, or in a Facebook post.

Well, the program that I use is Family Tree Maker v. 16, and it apparently can't do what Randy's RootsMagic can. I don't seem to have any function that counts the different trees and twigs in my database. On the other hand, I can count files manually, and I have 45 separate FTM family trees. My primary database has about 7,956 people in it. Some of the other trees are working subsets of my main tree, but most are other people's trees, either friends and extended family, people who have shared trees with me because they thought we were related, or people for whom I have done research. Some of the other trees are probably superfluous at this point, so it would probably be a good idea to move those out of the main folder and get them out of the way.

I've mentioned previously that I have several genealogy management programs installed on my computers (I'm bilingual: I use both Mac and PC). I've actually built three family trees in Reunion for people using Macs. The largest one of those has 131 people in it.

I think Reunion is the only other program I've actively used. I keep telling myself I'm going to look more at RootsMagic, especially since Randy keeps showing all the cool tricks it can do, but there are only 24 hours in a day.

Your mission this week, should you decide to accept it, is:

(1) How many different "trees" do you have in your genealogy management program (e.g., RootsMagic, Family Tree Maker, Reunion) or online tree (e.g., Ancestry Member Tree, MyHeritage tree)?

(2) How many trees do you have, and how big is your biggest tree? Do you have some smaller "bushes" or "twigs?"

(3) Tell us in your own blog post (please leave a link in Comments here), in a comment to this post, or in a Facebook post.

Well, the program that I use is Family Tree Maker v. 16, and it apparently can't do what Randy's RootsMagic can. I don't seem to have any function that counts the different trees and twigs in my database. On the other hand, I can count files manually, and I have 45 separate FTM family trees. My primary database has about 7,956 people in it. Some of the other trees are working subsets of my main tree, but most are other people's trees, either friends and extended family, people who have shared trees with me because they thought we were related, or people for whom I have done research. Some of the other trees are probably superfluous at this point, so it would probably be a good idea to move those out of the main folder and get them out of the way.

I've mentioned previously that I have several genealogy management programs installed on my computers (I'm bilingual: I use both Mac and PC). I've actually built three family trees in Reunion for people using Macs. The largest one of those has 131 people in it.

I think Reunion is the only other program I've actively used. I keep telling myself I'm going to look more at RootsMagic, especially since Randy keeps showing all the cool tricks it can do, but there are only 24 hours in a day.

Thursday, April 20, 2017

Treasure Chest Thursday: Who Has How Much Land?

These scans are of both sides of one sheet of 5" x 8" lined paper. The paper seems to be of moderate to poor quality. It has no watermark but does have a distinct texture, and I can see lines running vertically down the sheet. It was folded lengthwise. The writing is all in pencil. This looks like Jean La Forêt's handwriting to me.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

(Page 1)

E. Curdt to Alvina =

———

825.38' long - South side

452.53' wide – East side

827.84' – North side

450.83' – West side

8.569 Acres

8.571 acres

—————

Louisa Schaeffer's lot =

East side 461.52'

North Side 528.42' 5 1/2 acres

West Side 460.22'

South side 517.50'

—————

From Ashby Road to Mid. Golf Club.

distance 825.38 + 517.50 = 1342.88

For 5 acres it would take a slice

162 1/5 feet wide, from Ashby Road

to Midland Golf Club. –

—————

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

(Page 2)

Four acres = 174240 sq. ft

One acre = 43560 sq. feet

two — = 87120 ——"——

Five — = 217800 ——"——

———

If length 825 1/3 feet, it would

take a little over 105 feet in width.

——————————

5 acres South of Lot No. 10

from Ashby Road to Golf Club.

<drawing>

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

The first two sections of page 1 appear to be measurements of the land of Alvina Curdt (married Schulte) and Louisa Curdt (married Schaefer). Similar to some of the account figures I posted a few weeks ago, Jean came up with two different results for Alvina's acreage. Granted, there isn't much difference between the two — a mere .002 acres — but I have begun to question how good Jean really was with numbers. I admit I don't know how to compute the amount of land based on the figures he's given.

The distance from Ashby Road, which is where the family members lived, to the Midland Golf Club is the sum of the lengths of the south side of Alvina's lot and the south side of Louisa's lot, assuming that the unit of measurement here is feet. That's what he noted for Alvina and Louisa's lots, but I wish he had stated it here. Does that mean that Alvina's and Louisa's lots were adjacent to each other and ran between the road and the golf club? And what does it mean to say that it would take a piece 162 1/2 wide to make 5 acres? Why would he need or want to make 5 acres?

The top of the second page is nothing more than how many square feet are in one, two, four, and five acres, although not in that order. Maybe Jean wrote that as a reference for himself, as he worked out how many acres Alvina and Louisa had.

As for his next item, when I multiply 825.33333 by 105 feet, the result is 86,659.9997, just a little less than the 87,120 square feet Jean listed for two acres. Taking that from the other perspective, 87,120 feet divided by 825.33333 equals 105.557351, which is not what I would call "a little over" 105 feet; it's more than halfway to 106 feet. But it appears that Jean was thinking about 2 acres. On the other side of the page he noted the south side of Alvina's lot as being 825.38 feet. That 825.38 is almost the same as 825 1/3. When I multiply 825.38 by 105 feet, the result is 86,664.9, a little more than the previous number but still significantly short of 2 acres. Starting with the acreage, 87,120 feet divided by 825.38 is 105.551382, which is still closer to 106 than 105. Maybe he was trying to figure out 2 acres for Emma?

In the next section, with the simple drawing, Jean refers to 5 acres. Is this the same 5 acres he wrote about on the other side of the page? None of the numbers written by the drawing — 80, 25, 30 — match the figures he's used previously.

If I'm really lucky, something else in this folder will explain what all of this means.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

National Volunteer Week: What Can You Do to Help?

National Volunteer Week is a week of observance in the United States and Canada designed to spotlight the contributions volunteers make and to thank them for their efforts. In 2017 it will run from April 23 through April 29. In my little corner of the family history blog world, I regularly post about ways in which people can volunteer their time, talents, and more to help with various genealogy and history projects. So in honor of next week's event, it seemed like a good time to help publicize opportunities to help out.

A historian is researching the history of personal ads in the United States. She is looking for information about couples who met each other through a personal ad published in a newspaper any time between 1750 and 1950. If one of your ancestors or another family member met a husband or wife through a personal ad, or if you know of someone else who did, Francesca Beauman would love to hear the story. You can contact her by e-mail at francescabeauman@gmail.com. All information that is shared with her will be treated with the strictest confidence.

Researcher Mark Sy is working on a project about Dr. Ho Feng-Shan, a Chinese diplomat during World War II who issued thousands of exit visas to Austrian Jews fleeing the country after the Nazi invasion. Sy would like to communicate with survivors who received these visas, or their descendants, to learn about their plights and experiences during that time. This could be anyone who was living in Vienna from 1938–1940 and received a visa. Many of the refugees exiled to Shanghai ended up settling in North America, as several documents of survivors obtained from Yad Vashem and the Vancouver Holocaust Education Center reference early U.S. postal codes and New York ZIP Codes. Interviews so far have been conducted with individuals based in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Melbourne, but survivors and their descendants could be anywhere in the world. Please contact Mark at marksy85@gmail.com.

How much do you know about Colorado history? Maybe you can help solve the mystery of the woman in the portrait. At the Colorado State Archives, while cleaning up after a leak in a storage area, several old portraits of former Colorado governors were found, along with one portrait of a woman. The problem is that no one has any idea who the woman is. The local NBC affiliate covered the story, and the reporter posted about it on his Facebook page, but so far no one has come up with the answer.

Speaking of history, the Pioneer Village Museum in Beausejour, Manitoba is asking people to help identify early 20th-century photographs from the area, about 30 miles east of Winnipeg. The photographs are being scanned from negatives that were donated to the museum after the woman who had them passed away. So far the photos appear to range from about 1900 to the 1930's. One man actually recognized himself in a photo! The museum is looking for identification of people or locations in the photographs, which are being posted to Facebook.

Another repository seeking help in identifying people in photographs is the Oak Ridge Public Library in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The photos were taken by resident Ruth Carey from the 1960's to April 1994 and were donated to the library, along with many undeveloped negatives, by Carey's daughter. Some of the prints and negatives have been digitized, but the majority have not and must be viewed in person at the library. Carey apparently was Jewish, and a good number of the photographs are of the Jewish community in Oak Ridge.

About 30 some odd years ago, a man living in Hrodna, Belarus (formerly Grodno in Russia and Poland) discovered two albums with photographs and letters in the attic of the building in which he was living. Some of the photos have writing in Polish and Hebrew, and the names Konchuk/Kanchuck and Vazvutski appear. The items were likely left in the building, which seems to have been in the Jewish section of the city, before or during World War II. The man is now trying to find family members to return the items. There's a long article in Byelorusian about the story (here's the Google Translate version), but apparently without contact information. A woman who has posted about this on Facebook seems to be functioning as a contact person.

Two more photos that are currently unidentified arrived at the Belleville (Illinois) Labor & Industry Museum with a donation of printing materials. Each of the photographs is of an individual (one man, one woman) laid out in a casket for viewing. The museum is asking people to look at the photos and call if they can provide any information.

This year, the West Midlands Police (main office in Birmingham, England) celebrates the 100th anniversary of its first female officers, who joined the force in April 1917. Three female officers in an archive photograph are unidentified, and files on four of the early officers have not survived. The force is looking for help from the public in identifying the unknown faces in the photo and in gathering any information on these pioneering policewomen.

Not all photographs are unidentified, which is a good thing. If you have any family connections to Truro, Nova Scotia, particularly from 1967 to the late 1980's, you might want to contact Carsand Photo Imaging. The company is owned by the son of the late Carson Yorke, who founded Carsand-Mosher Photographic. The elder Yorke kept all the negatives of portraits he took during the aforementioned years, and his son, Colin Yorke, is now trying to reunite images with families. Colin Yorke is apparently taking contacts primarily through his company's Facebook page, but you should be able to get in touch with him through the company's Web site if you don't use Facebook.

The University of South Florida at St. Petersburg is looking for donations of back issues of The Weekly Challenger, the historic black newspaper of Pinellas County, from 1967 through the 1990's. Even clippings can be helpful. The newspapers will be digitized to create an archive. Contact information is in the article linked above, as is a link to a recording of a lecture about the Weekly Challenger digital initiative.

When I teach about online newspapers, I discuss the problems that optical character recognition (OCR) software has with reading old newspapers due to ink bleed, typeface dropout, damaged pages, and other problems. Something I've never considered is whether the software has problems recognizing old fonts. That issue apparently did arise for Iowa State University when it digitized its yearbooks for 1894–1994 (except 1902). Because of that, and to have the content be more accessible (as in ADA) online, Iowa State is asking volunteers to help "Transcribe the 'Bomb' " (the name of the yearbook is The Bomb). An article has information about the digitization project and a link to the volunteer site.

Dr. Ciaran Reilly is coordinating the Irish Famine Eviction Project to document evidence of evictions between 1845 and 1851. His vision is to create a dedicated online resource listing GPS coordinates for famine eviction sites and to create a better understanding of the people involved in the evictions. It is hoped that the project will shed new light on numbers, locations, and background stories of those involved.

Sponsored by Irish Newspaper Archives, the project will use primary and secondary source information to research, gather, and catalog evictions. One of the goals is to collaborate with individuals, societies, and libraries across the world. The project is looking for any information about evictions, locations, and local folklore.

To see the 500 sites that have been mapped so far, visit https://irishfamineeviction.com/eviction-map/. To submit your own research for inclusion in the project, e-mail your findings to famineeviction@gmail.com or tweet @famineeviction.

Writer David Wolman wants to have a huge party with descendants of the approximately 600 passengers (most of whom were Irish) rescued from the sinking ship Connaught in October 1860. Failing that, he would at least like to make contact with any of those descendants. Wolman recently published a story about the rescue of the Connaught's passengers and a modern-day treasure hunter who wanted to find the shipwreck, and issued an invitation to contact him via e-mail or Twitter. A list of the passengers is in a New York Times article available online.

I don't usually post stories that have already appeared on Eastman's blog, because he has much, much wider readership than I do, but this one is important enough that I felt I should (because I know not everyone reads Eastman). Extreme Relic Hunters, a company that specializes in World War I and World War II relic retrieval, discovered a huge cache of WWII dog tags (more than 12,000!). The majority are from British servicemen, but there are some from other countries. Of the British, almost all are from Royal Armoured Corps, Royal Tank Regiment, or Reconnaissance, with no RAF or Navy personnel. The guys from the company want to reunite as many of these dog tags with family members as humanly possible (one was returned to the veteran himself). You can read about the discovery and the project to return the dog tags on the Forces War Records and the Extreme Relic Hunters sites. Oh, and Extreme Relic Hunters is looking for volunteers to help them with the return project; they're just a little overwhelmed.

If you have not read about it yet, well known genealogy speaker Thomas MacEntee has posted a survey to learn what family historians and genealogists think of the industry today and what they would like it to be. Read about it here and then click the link to take the survey. He promises that your e-mail address will not be saved and you will not be contacted.

A historian is researching the history of personal ads in the United States. She is looking for information about couples who met each other through a personal ad published in a newspaper any time between 1750 and 1950. If one of your ancestors or another family member met a husband or wife through a personal ad, or if you know of someone else who did, Francesca Beauman would love to hear the story. You can contact her by e-mail at francescabeauman@gmail.com. All information that is shared with her will be treated with the strictest confidence.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

|

| Ho Feng-Shan |

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

How much do you know about Colorado history? Maybe you can help solve the mystery of the woman in the portrait. At the Colorado State Archives, while cleaning up after a leak in a storage area, several old portraits of former Colorado governors were found, along with one portrait of a woman. The problem is that no one has any idea who the woman is. The local NBC affiliate covered the story, and the reporter posted about it on his Facebook page, but so far no one has come up with the answer.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Speaking of history, the Pioneer Village Museum in Beausejour, Manitoba is asking people to help identify early 20th-century photographs from the area, about 30 miles east of Winnipeg. The photographs are being scanned from negatives that were donated to the museum after the woman who had them passed away. So far the photos appear to range from about 1900 to the 1930's. One man actually recognized himself in a photo! The museum is looking for identification of people or locations in the photographs, which are being posted to Facebook.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Another repository seeking help in identifying people in photographs is the Oak Ridge Public Library in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The photos were taken by resident Ruth Carey from the 1960's to April 1994 and were donated to the library, along with many undeveloped negatives, by Carey's daughter. Some of the prints and negatives have been digitized, but the majority have not and must be viewed in person at the library. Carey apparently was Jewish, and a good number of the photographs are of the Jewish community in Oak Ridge.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

About 30 some odd years ago, a man living in Hrodna, Belarus (formerly Grodno in Russia and Poland) discovered two albums with photographs and letters in the attic of the building in which he was living. Some of the photos have writing in Polish and Hebrew, and the names Konchuk/Kanchuck and Vazvutski appear. The items were likely left in the building, which seems to have been in the Jewish section of the city, before or during World War II. The man is now trying to find family members to return the items. There's a long article in Byelorusian about the story (here's the Google Translate version), but apparently without contact information. A woman who has posted about this on Facebook seems to be functioning as a contact person.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Two more photos that are currently unidentified arrived at the Belleville (Illinois) Labor & Industry Museum with a donation of printing materials. Each of the photographs is of an individual (one man, one woman) laid out in a casket for viewing. The museum is asking people to look at the photos and call if they can provide any information.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

This year, the West Midlands Police (main office in Birmingham, England) celebrates the 100th anniversary of its first female officers, who joined the force in April 1917. Three female officers in an archive photograph are unidentified, and files on four of the early officers have not survived. The force is looking for help from the public in identifying the unknown faces in the photo and in gathering any information on these pioneering policewomen.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Not all photographs are unidentified, which is a good thing. If you have any family connections to Truro, Nova Scotia, particularly from 1967 to the late 1980's, you might want to contact Carsand Photo Imaging. The company is owned by the son of the late Carson Yorke, who founded Carsand-Mosher Photographic. The elder Yorke kept all the negatives of portraits he took during the aforementioned years, and his son, Colin Yorke, is now trying to reunite images with families. Colin Yorke is apparently taking contacts primarily through his company's Facebook page, but you should be able to get in touch with him through the company's Web site if you don't use Facebook.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

The University of South Florida at St. Petersburg is looking for donations of back issues of The Weekly Challenger, the historic black newspaper of Pinellas County, from 1967 through the 1990's. Even clippings can be helpful. The newspapers will be digitized to create an archive. Contact information is in the article linked above, as is a link to a recording of a lecture about the Weekly Challenger digital initiative.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

When I teach about online newspapers, I discuss the problems that optical character recognition (OCR) software has with reading old newspapers due to ink bleed, typeface dropout, damaged pages, and other problems. Something I've never considered is whether the software has problems recognizing old fonts. That issue apparently did arise for Iowa State University when it digitized its yearbooks for 1894–1994 (except 1902). Because of that, and to have the content be more accessible (as in ADA) online, Iowa State is asking volunteers to help "Transcribe the 'Bomb' " (the name of the yearbook is The Bomb). An article has information about the digitization project and a link to the volunteer site.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Dr. Ciaran Reilly is coordinating the Irish Famine Eviction Project to document evidence of evictions between 1845 and 1851. His vision is to create a dedicated online resource listing GPS coordinates for famine eviction sites and to create a better understanding of the people involved in the evictions. It is hoped that the project will shed new light on numbers, locations, and background stories of those involved.

Sponsored by Irish Newspaper Archives, the project will use primary and secondary source information to research, gather, and catalog evictions. One of the goals is to collaborate with individuals, societies, and libraries across the world. The project is looking for any information about evictions, locations, and local folklore.

To see the 500 sites that have been mapped so far, visit https://irishfamineeviction.com/eviction-map/. To submit your own research for inclusion in the project, e-mail your findings to famineeviction@gmail.com or tweet @famineeviction.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

Writer David Wolman wants to have a huge party with descendants of the approximately 600 passengers (most of whom were Irish) rescued from the sinking ship Connaught in October 1860. Failing that, he would at least like to make contact with any of those descendants. Wolman recently published a story about the rescue of the Connaught's passengers and a modern-day treasure hunter who wanted to find the shipwreck, and issued an invitation to contact him via e-mail or Twitter. A list of the passengers is in a New York Times article available online.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

I don't usually post stories that have already appeared on Eastman's blog, because he has much, much wider readership than I do, but this one is important enough that I felt I should (because I know not everyone reads Eastman). Extreme Relic Hunters, a company that specializes in World War I and World War II relic retrieval, discovered a huge cache of WWII dog tags (more than 12,000!). The majority are from British servicemen, but there are some from other countries. Of the British, almost all are from Royal Armoured Corps, Royal Tank Regiment, or Reconnaissance, with no RAF or Navy personnel. The guys from the company want to reunite as many of these dog tags with family members as humanly possible (one was returned to the veteran himself). You can read about the discovery and the project to return the dog tags on the Forces War Records and the Extreme Relic Hunters sites. Oh, and Extreme Relic Hunters is looking for volunteers to help them with the return project; they're just a little overwhelmed.

-- >< -- >< -- >< -- >< --

If you have not read about it yet, well known genealogy speaker Thomas MacEntee has posted a survey to learn what family historians and genealogists think of the industry today and what they would like it to be. Read about it here and then click the link to take the survey. He promises that your e-mail address will not be saved and you will not be contacted.

Saturday, April 15, 2017

Saturday Night Genealogy Fun: Who in Your Database Has Your Birthday?

In this week's challenge for Saturday Night Genealogy Fun, Randy Seaver has us crunching data in our genealogy databases:

Your mission this week, should you decide to accept it, is to:

(1) Are there persons in your genealogy database who have the same exact birth date that you do? If so, tell us about them — what do you know, and how are they related to you?

(2) Are there persons in your database who are your ancestors and share your birthday (but not the year)? How many, and who are they?

(3) Are there other persons in your database who share your birthday (but not the year)? How many, and who are they?

(4) For bonus points, how did you determine this? What feature or process did you use in your software to work this problem out? I think the Calendar feature probably does it, but perhaps you have a trick to make this work outside of the Calendar function.

(5) Share your answers on your own blog, in a comment to this post, or on Facebook or Google+. Be sure to leave a link in Comments to your post.

So here's my little data dump.

(1) No one in my database has the exact same birthday that I do, April 9, 1962 (my birthday was a week ago Sunday). Like Randy, I didn't really expect to find anyone.

(2) None of my ancestors for whom I have complete birthdates was born on April 9.

(3) Of the people in my database for whom I have complete birthdates (I don't know how many that is), only six persons were also born on April 9, and they're all in the 20th century.

• April 9, 1907, George Wendel Votaw, 4th cousin twice removed

• April 9, 1917, Anna Marie Stayton, grand-aunt-in-law

• April 9, 1945, Cecelia Keselman, ex-4th cousin-in-law

• April 9, 1980, Patricia Marie Gauntt, 2nd cousin

• April 9, 1995, Jacob Berkowitz, 3rd cousin

• April 9, 1996, Yoni Monat, 3rd cousin

The only one I remembered beforehand is my cousin Yoni. I do have several people with only the month of April and no specific day, so it's possible there are a few more. I so need to have time to work on my own family research.

(4) This did not work as well as it should have. I use Family Tree Maker v. 16, which does have a calendar function. Unfortunately, when I ran it, it gave me 57 copies of each month, and every single one was empty, even though I double-checked to make sure it was supposed to be searching through the entire database. So I had to do a manual search in the birthdate field. For my search term I used "April 9." Also unfortunately, this too did not work as well as I had hoped. It picked up all birthdates that started with "about", "before", and "between" and anything with just a year. Altogether, I paged through 1,806 entries to come up with my list of six people. You could say I'm a little . . . disappointed in FTM's performance.

My database, by the way, has only 7,956 individuals in it, as compared to Randy's 47,500 (which I am just astounded at!). Randy had .14% of the people in his database with the same birthdate but a different year. For me the figure was .07% of my database with the same birthdate. Pretty small numbers there for both of us.

Your mission this week, should you decide to accept it, is to:

(1) Are there persons in your genealogy database who have the same exact birth date that you do? If so, tell us about them — what do you know, and how are they related to you?

(2) Are there persons in your database who are your ancestors and share your birthday (but not the year)? How many, and who are they?

(3) Are there other persons in your database who share your birthday (but not the year)? How many, and who are they?

(4) For bonus points, how did you determine this? What feature or process did you use in your software to work this problem out? I think the Calendar feature probably does it, but perhaps you have a trick to make this work outside of the Calendar function.

(5) Share your answers on your own blog, in a comment to this post, or on Facebook or Google+. Be sure to leave a link in Comments to your post.

So here's my little data dump.

(1) No one in my database has the exact same birthday that I do, April 9, 1962 (my birthday was a week ago Sunday). Like Randy, I didn't really expect to find anyone.

(2) None of my ancestors for whom I have complete birthdates was born on April 9.

(3) Of the people in my database for whom I have complete birthdates (I don't know how many that is), only six persons were also born on April 9, and they're all in the 20th century.

• April 9, 1907, George Wendel Votaw, 4th cousin twice removed

• April 9, 1917, Anna Marie Stayton, grand-aunt-in-law

• April 9, 1945, Cecelia Keselman, ex-4th cousin-in-law

• April 9, 1980, Patricia Marie Gauntt, 2nd cousin

• April 9, 1995, Jacob Berkowitz, 3rd cousin

• April 9, 1996, Yoni Monat, 3rd cousin

The only one I remembered beforehand is my cousin Yoni. I do have several people with only the month of April and no specific day, so it's possible there are a few more. I so need to have time to work on my own family research.

(4) This did not work as well as it should have. I use Family Tree Maker v. 16, which does have a calendar function. Unfortunately, when I ran it, it gave me 57 copies of each month, and every single one was empty, even though I double-checked to make sure it was supposed to be searching through the entire database. So I had to do a manual search in the birthdate field. For my search term I used "April 9." Also unfortunately, this too did not work as well as I had hoped. It picked up all birthdates that started with "about", "before", and "between" and anything with just a year. Altogether, I paged through 1,806 entries to come up with my list of six people. You could say I'm a little . . . disappointed in FTM's performance.

My database, by the way, has only 7,956 individuals in it, as compared to Randy's 47,500 (which I am just astounded at!). Randy had .14% of the people in his database with the same birthdate but a different year. For me the figure was .07% of my database with the same birthdate. Pretty small numbers there for both of us.

Thursday, April 13, 2017

Treasure Chest Thursday: A Note about Settling Elizabeth Curdt's Estate

This, believe it or not, is a calling card that is 3 3/4" x 2 1/4". It is made of fairly heavy card stock. It is yellowish-brown and seems to have some staining or discoloration, perhaps due to age. A newspaper clipping has been pasted over printing on the front of the card, and handwritten notes are on the back.

Underneath the newspaper clipping on the top image is Jean La Forêt's calling card after he retired from the Marine Corps. I was unable to scan it due to the way the clipping is pasted on the card. The text reads (in a beautiful script font):

Jean L. La Forêt

N. C. Staff Officer, U. S. M. C., Ret'd.

The newspaper clipping is not dated and does not state from which newspaper it came. It probably ran for the first time on August 25, 1920, the date at the bottom of the notice, but these notices often ran for several days.

On the back of the card are some notes in what appears to be Jean's handwriting:

Settled 8-10-20

————

Accepted Check

for 119 98/00 dal.[?]

——————

Personal estate of

Eliz. Curdt .

—————

On Jean's calling card, U.S.M.C. is obviously United State Marine Corps, but I don't know what N. C. is an abbreviation for. It does not appear in the Unofficial Unabridged Dictionary for Marines or as anything that makes sense in context in Acronym Finder's list of military and government abbreviations. Can someone enlighten me, please?

Because Jean retired twice from the Marines — once before he served as a Vice Consul and again after he re-upped to serve during World War I — this card could date from either time. Whichever it is, there's nothing to indicate how old it was when he used it as a notecard for pieces of information relating to settling Elizabeth Curdt's estate.

August W. Curdt is listed as the administrator, as he was in Jean's accounting notes. August was Emma (Schafer) La Forêt's half-brother from her mother's second marriage, to Louis Curdt.

The notice states that the final settlement of the estate was to take place on the second Monday in August 1920. According to Jean's accounting notes and to the notes on the reverse of this card, however, it was settled on August 10, 1920, which apparently was a Tuesday.

Jean noted the amount of the check accepted, presumably by Emma, as 119.98. I'm pretty sure I have read the letters after the figure correctly — dal. — but I don't understand what that means after the amount of the check.

In Jean's accounting notes, he wrote that the check August gave to Emma was $119.94. Somehow I don't think the apparent extra four cents made him very happy, considering that he wrote that he believed Emma was due $133.35. But I don't understand why there are two different figures.

Jean has usually appeared very careful in his notes that I've looked at previously, even down to the exact dates of his enlistments. I'm surprised at the differences in the figures in his accounting notes and now in what he noted as the amount of the settlement check. Perhaps they're an indication of Jean's mental state during all of these shenanigans.

And in case anyone is wondering why there was no Treasure Chest Thursday post last week, it was not because I was lolling around and taking the night off. We had another heavy storm go through the San Francisco Bay area that evening, and it knocked out my power before 7:00 p.m. I didn't get a text that the power was restored until almost 12:30 a.m. At that point it was already Friday morning, so I decided against a late post. So I'm putting the blame on PG&E!

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Monday, April 10, 2017

Learning a Little More about Sikh Family History Traditions

When I have met people of Sikh ancestry here in the United States, most of them are far enough removed from traditions in Punjab and India that they have not known "how things worked", such as naming practices, who keeps family information, etc., which of course drove this genealogist nuts. I lucked out last week and found someone who knew a little more and was generous enough to add to my small accumulation of information.

Previously, I knew that men carry the last name Singh ("lion") and women have the name Kaur ("princess"), but that family names exist also. I had been told that the tradition was for a man to use the name Singh until he married, so someone might be known as Karam Singh. When he married, Singh would become his middle name and he would add his family name, e.g., Karam Singh Sandhu.

I had always wondered what happened with the women's names. My guess was that when a woman married, she probably added her husband's family name after Kaur. So if Raj Kaur married Karam Singh, her name would become Raj Kaur Sandhu.

The woman I spoke to last week had a hyphenated last name and a middle name of Kaur. Well, I know Kaur is associated with Sikhs. We had a few minutes, so I asked if she minded me being nosy. Lucky me, she said it was ok! I told her the few bits I just wrote about above and in particular that I was wondering about her hyphenated last name after Kaur.

She started out by saying that one of the original ideas behind Sikhism was to eradicate the castes, so that everyone was equal. That reasoning was behind the names of Singh for men and Kaur for women — everyone would have the same names, no name could take precedence, everyone would be equal. No surprise, not everyone was on board with this concept, and so, she told me, three different naming traditions now exist.

Those individuals who thought "no castes" was a great idea took on Singh and Kaur, and that's all they used. They left behind the family names. So you had the name Singh, and when you married you were still a Singh.

Many people of higher castes weren't as willing to give their names up. Some who maintained family names used the system I had already learned about, where you take on the family name after marriage. But some, such as the family of the woman I met, used the family name from birth. So if a family used this tradition, Karam's name would always have been Karam Singh Sandhu.

What was particuarly amusing about this woman's specific situation is that her hyphenated name was a combination of her family name and that of her husband, who is Muslim. The naming tradition with which he is familiar dictates that when a woman marries, she takes her husband's given name as her middle name and his family name as her own. So if I use the names from above as examples (even though they are Sikh names), Raj Kaur would have become Raj Karam Singh (or possibly Sandhu) on marrying Karam Singh. The reason my acquaintance maintained her own name is that her college degrees are in that name and she was already an established professional. She told her husband there was no way she was negating that by taking his name and dropping her own. As a thoroughly modern woman, but one with knowledge of her people's history, she created her own tradition.

I also discovered last week that there are indeed Sikh family genealogists! When I learned about Hindu family genealogists on the Sanjay Gupta segment of Finding Your Roots in 2012, I suggested at the time that it could mean Sikh family genealogists existed, especially for prominent families. Well, I was looking up something on Wikipedia, and it led me to another page, and somehow I found a page about Mirasi, the genealogists of India and Pakistan. The section on the Mirasi of Indian Punjab specifically mentions Sikh subgroups. Of course, I still don't speak or read Punjabi, Urdu, or any other Indian languages, so it might be difficult for me to communicate with any of these genealogists if I could find them, but I definitely think progress is being made! One of these days, I am convinced I will find more family information for my stepsons' grandfather (and maybe even prove that their great-great-grandfather really was the headman of the village).

Previously, I knew that men carry the last name Singh ("lion") and women have the name Kaur ("princess"), but that family names exist also. I had been told that the tradition was for a man to use the name Singh until he married, so someone might be known as Karam Singh. When he married, Singh would become his middle name and he would add his family name, e.g., Karam Singh Sandhu.

I had always wondered what happened with the women's names. My guess was that when a woman married, she probably added her husband's family name after Kaur. So if Raj Kaur married Karam Singh, her name would become Raj Kaur Sandhu.

The woman I spoke to last week had a hyphenated last name and a middle name of Kaur. Well, I know Kaur is associated with Sikhs. We had a few minutes, so I asked if she minded me being nosy. Lucky me, she said it was ok! I told her the few bits I just wrote about above and in particular that I was wondering about her hyphenated last name after Kaur.

She started out by saying that one of the original ideas behind Sikhism was to eradicate the castes, so that everyone was equal. That reasoning was behind the names of Singh for men and Kaur for women — everyone would have the same names, no name could take precedence, everyone would be equal. No surprise, not everyone was on board with this concept, and so, she told me, three different naming traditions now exist.

Those individuals who thought "no castes" was a great idea took on Singh and Kaur, and that's all they used. They left behind the family names. So you had the name Singh, and when you married you were still a Singh.

Many people of higher castes weren't as willing to give their names up. Some who maintained family names used the system I had already learned about, where you take on the family name after marriage. But some, such as the family of the woman I met, used the family name from birth. So if a family used this tradition, Karam's name would always have been Karam Singh Sandhu.

What was particuarly amusing about this woman's specific situation is that her hyphenated name was a combination of her family name and that of her husband, who is Muslim. The naming tradition with which he is familiar dictates that when a woman marries, she takes her husband's given name as her middle name and his family name as her own. So if I use the names from above as examples (even though they are Sikh names), Raj Kaur would have become Raj Karam Singh (or possibly Sandhu) on marrying Karam Singh. The reason my acquaintance maintained her own name is that her college degrees are in that name and she was already an established professional. She told her husband there was no way she was negating that by taking his name and dropping her own. As a thoroughly modern woman, but one with knowledge of her people's history, she created her own tradition.

I also discovered last week that there are indeed Sikh family genealogists! When I learned about Hindu family genealogists on the Sanjay Gupta segment of Finding Your Roots in 2012, I suggested at the time that it could mean Sikh family genealogists existed, especially for prominent families. Well, I was looking up something on Wikipedia, and it led me to another page, and somehow I found a page about Mirasi, the genealogists of India and Pakistan. The section on the Mirasi of Indian Punjab specifically mentions Sikh subgroups. Of course, I still don't speak or read Punjabi, Urdu, or any other Indian languages, so it might be difficult for me to communicate with any of these genealogists if I could find them, but I definitely think progress is being made! One of these days, I am convinced I will find more family information for my stepsons' grandfather (and maybe even prove that their great-great-grandfather really was the headman of the village).

Sunday, April 9, 2017

"Who Do You Think You Are?" - Jennifer Grey

I knew I was going to fall further behind on my Who Do You Think You Are? posts, but I'll just keep plugging away. At least I haven't missed seeing any of the episodes so far.

I was looking forward to the Jennifer Grey episode, not only because I know who she is but because I enjoy seeing what they do with Jewish research. The teaser told us that Grey would shatter the darkness surrounding the grandfather she never understood. She would find a family that endured a heartbreaking tragedy and learn about an extraordinary, mysterious ancestor whose remarkable story would turn everything she believed about her grandfather on its head.

Jennifer Grey is shown in Manhattan, and we see her in seems to be her apartment (although her Wikipedia page says she lives in Venice, California, at least as of 2008). She mentions that she just finished wrapping the second season of Red Oaks for Amazon. The only other acting credit mentioned is Dirty Dancing, which not only launched her to fame but also defined her as a dancer in the public eye, to the point that she became self-conscious about dancing and stopped doing it for twenty years. She was asked to participate in Dancing with the Stars but didn't consider it until her daughter convinced her to do it, saying that she wanted her to have the experience. She won the competition, and after coming back to dance after twenty years without it, she wondered what else she had been missing out on. She became curious about her life and family history.

Grey was born in 1960 to Jo Wilder (the stage name of Joanne Carrie Brower) and Joel Grey, who was just beginning his Broadway career at the time. She knows little about her family beyond her parents and jokes about being a bad Jew, saying she wasn't curious enough. She knows more about her father's side of the family; they were entertainers and "show people" and were more involved in her family's life. Her mother's parents, Clara and Izzie Brower, were the antithesis of her father's parents. She doesn't remember much about them, almost as if they were ghosts.

Grey remembers that Izzie was a pharmacist in Brownsville, a Brooklyn neighborhood. She did know him but remembers only a few things. When he came to visit he seemed depressed to her. He wore heavy coats that smelled of mothballs and he always brought a box of pastry tied with a string. She felt aloof around him. He looked beaten down and as if he were from another world and time. Now she wonders why he looked so sad.

She wants to learn about Izzie on the journey she's going to take. She wonders how old he was when he came to the United States. What was his life like? What kind of adversity did he face?

One story Grey remembers hearing is that Izzie was a little boy when he was made to leave Russia in a hurry and came to America. He had to wear a heavy coat lined with the family silverware. She figures he must have had a rough life but doesn't know why or where he left from, just that the family were Russian Jews.

Grey asked her mother for what information she knew about the family, and in response her mother sent a packet. She sits down to open it with her daughter, Stella Gregg, whom she tells that she didn't want to open it by herself. The first thing she takes out of the envelope is a letter, and she puts on her glasses to read it. The editing has her reading bits and pieces out of order (as usual on these programs), but this is almost the entire letter:

Dear Jennifer

When I heard you were taking this journey I was so pleased. Sitting down to write this letter has really [——] memories. I am including some information here that should get you started. I've also sent along a few [photos?] that you may or may not have seen.

My dad, Israel or "Izzie" as he was called, came to New York from the Ukraine (though I don't know [where?] specifically) with his father, your great grandfather, Solomon, a tall stately fellow. I believe I've heard [——] mill back in the old country. My father's job on the journey over was to wear a black coat fitted with [pockets in?] which he carried family silverware. The picture of this young boy, laden with this weight he was responsible [for? —] comical and a little Chaplin-esque.

Our lives were lived on one block: Bristol St between Pitkin and Sutter in Brownsville, Brooklyn. We [the rest of this paragraph was not shown]

At my father's pharmacy, they called him "doctor." It was on the corner of Sutter and Bristol and a lot of my young life was spent there. In the summer, I'd be swinging from the [—] bars and sitting in a sling chair out front on the street, or running to call people to one of the payphones, in the store, because people didn't have their own phones at the time - I don't know if you know this, but your grandmother, Clara, also graduated from pharmacy school, though she never practiced.

It's sad that you didn't have more of a relationship with your grandpa Izzie, but I understand why you didn't. You were a kid, and he didn't quite understand the world we were living in, our lifestyle at the time. I fault myself now for having not been more inclusive. I guess we were very selfishly into our own world and building our family. I don't know if you remember, but when you were a kid, I drove you to my old neighborhood to look for Izzie's pharmacy. It was all pretty grim. His store, what was left of it, was literally charred. I think you were too startled and young at the time to really know what you were looking at.

I hope that this experience will offer you a greater understanding of where your relatives came from and how strong they were to come to a frightening new land where they didn't speak the language and didn't know the mores of this place. I'm more impressed after writing this than I was before. I mean, we look back and feel sad that we didn't appreciate things more. I feel like my dad was an emotional person but I didn't give him enough credit for that, nor did you get to see that side of him. Perhaps you'll get to know him on this journey and find a new appreciation for him. I know he'd appreciate who you have become...

Love, Mom

P.S. I never knew your great grandmother, Izzie's mother (Solomon's wife.) I don't even know her name! Clearly she died, but I don't know where or when. Maybe you'll find out?

Grey becomes emotional at a couple of points, particularly where her mother wrote that she regretted not making more of an effort to include Izzie in the family. She moves from the letter to the photographs that her mother sent. The first shown is of Izzie and Clara with their children, Grey's Uncle Mitchell and her mother as a baby in Izzie's arms. The latter gets Grey and Stella joking about "Bubbie as a baby" and "Baby Bubbie." (Bubbie is Yiddish for grandmother and is what I called my maternal grandmother.)

The second photo is of two boys in front of Izzie's pharmacy. Grey proudly reads "Israel Brower, Pharmacist, Chemist." (There was handwriting in the lower right corner of the photo. I think it said "Mitchell Brower", who was probably one of the boys, but it wasn't shown on screen long.)

The last photo shown looks like a big family reunion. A title at the top reads "BROWER FAMILY 1937", and Grey's mother has given some information and labeled some of the people in the photo:

This photo was taken in 1937 at 107 Bristol Street in Brownsville, Brooklyn. (I wonder [the rest of this sentence was not shown on screen]

I numbered the immediate family.*

1. Israel 'Izzie' Brower, your grandfather

2. William, your great uncle, Izzie's older brother

3. Tillie, your great aunt, Izzie's younger sister

4. Mitchell, your uncle (my brother)

5. Me, your mom.

6. Sylvia, your great aunt

*Not in the photo: Rose, Israel's older sister, and Charlie, his younger brother. (Both died quite young.)

Grey really likes this last photo and is surprised that her mother has never shared it before. (It's a great photo to have!) She's curious why there's so little information about the family before they came to the United States. Even her mother doesn't know. Stella suggests that maybe Izzie and Clara didn't share the information, and Grey says she hopes that doesn't happen with Stella.

We don't get a cue from the scene with Stella saying where Grey would go next. We simply see her in the next segment walking, and she tells us that "she has contacted a historian" (after being told to do so by the producers, of course) who specializes in American Jews. They are going to meet at the Brooklyn Public Library in Brownsville (the Stone Avenue branch, to be specific), the neighborhood where her grandparents lived, and maybe even where her mother went to the library.

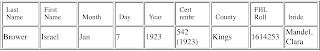

Inside the library is Dr. Annie Polland, credited as an American Jewish historian with the Tenement Museum. (She's the Senior Vice President of Education and Programs at the museum.) The first thing Grey asks is why her family knows so little about what happened prior to the United States. Polland explains that it is common for children and grandchildren not to know much. She quotes a saying — "What the son wishes to forget, the grandson wishes to remember" (known as Hansen's law) — and adds that sometimes people wait too too late to find the information. Undeterred, Grey says that she doesn't know when Izzie arrived in the United States. Polland has a laptop handy and tells Grey to search on Ancestry.com (12 minutes in, the longest so far this season). She has Grey go to the Immigration & Travel collection and then to the New York Passenger Lists database. All Grey enters is Israel Brower. Although Grey knows nothing other than Izzie's name, conveniently Polland knows more and points her to the second result on the list, even though the name is spelled "Braver." Polland says that the spelling is the "Russian version of Brower", which is a somewhat questionable explanation.

So Grey clicks on the link, and up pops a passenger list from January 16, 1907 for the Pretoria, which departed from Hamburg. Grey finds Israel Braver on the list, and he is traveling with three other people: Rose, Cheskel, and Taube. (They're on the last four lines of the image below.)

Israel was 16 years old, and Grey does the math to determine he was born in 1891 (which Polland does not tell her is approximate, unfortunately). His occupation is listed as compositor, which Polland explains was someone who set type for printing; it was a skilled position. He probably served an apprenticeship to gain his training.

Looking over the names of the individuals traveling with her (unproven) grandfather, Grey recognizes Rose as her grandfather's older sister, but she is confused by Cheskel and Taube. Polland explains that Jews coming to the United States generally had their Yiddish names on the passenger lists but once they arrived they often "Americanized" their old-country names. So it appears that Cheskel became Charles, while Taube chose to call herself Tillie.

As she reads the information in the other columns on the passenger list, Grey sees that the siblings' last residence is listed as Yampol and that they said they were going to join their father Solomon (called Schulem, which generated more discussion about Jewish names) at an address in Brooklyn. Grey realizes someone is missing and asks where their mother was. She recalls that in her letter, her own mother had said she did not know the name of Solomon's wife.

Grey is now visibly distressed (or is putting on a good act, because she is, after all, an actress). The four siblings, the youngest of whom is only 9, would have traveled at least two weeks on the ship, with no parent beside them. Grey starts asking one question after another: Why didn't their mother come with them? Did she not want to come? Was she already in the U.S.? Illegally? Had she died in childbirth? Was there some other way to find her?

Polland says that they can look at the censuses for other family members, which could possibly tell if the mother had joined the family later. The first census after the siblings' 1907 arrival was in 1910. Instead of going to Ancestry again, Grey asks if the census pages can be printed, because she likes to hold paper in her hands. (I'm not sure if this was bad editing and Grey made her request after they had found census entries online, or if Grey was simply jumping the gun, assumed that Polland already knew about census pages, and was trying to avoid working on the computer again. Either way, it came off as a non sequitur.) Polland says it won't be a problem and disappears momentarily, reappearing with papers in hand. The only page discussed or shown on air is the 1910 census.

In the 1910 census they find Solomon Brower (46 years old), an older son named William, and the four siblings seen on the passenger list. Grey notes that there is still no mother. When she checks the box for marital status for Solomon, she finds "Wd", for widowed. So that's why Grey's mother didn't know her name and why she didn't come — she was dead. (That, of course, is an assumption on her part. She could have come with Solomon and died in New York.) Then she goes back to fretting about the four siblings coming over on the ship all alone with no mother.

Polland points out that the census is like a little novel, because it tells you what people were doing at a given time, such as jobs or school. When Grey looks for Izzie's occupation, she finds that it says he could speak English and that he was working as a compositor for a printing company. Now that she has seen this for a second time, she decides she's a little confused. Everything she knows about Izzie is when he had the pharmacy. So how and why did he change from working in printing to being a pharmacist?

For how he became a pharmacist, Polland says there was one school, the Brooklyn College of Pharmacy, so that's where he probably went. Grey makes a comment about whether it still exists, and Polland tells her it is now part of Long Island University. So that's where Grey is going next.

(This really caught my attention, because I've done research on someone who graduated from the Brooklyn College of Pharmacy, and I had already learned that it's now part of LIU. So I was particularly looking forward to seeing what documents the show had found relating to Izzie.)

As she leaves the library, Grey is thinking about Izzie and his sad-sack face. If she had known that his mother had died, she would have acted differently. She wants to tell her daughter so that she'll have some compassion for Izzie also. The children lost their mother, but the family forged on and made a new life. (And, of course, she's assuming that mom was someone whom the children missed. We'll never know if she was a shrew or a harridan and everyone silently was thankful that she was gone. But everyone becomes a saint when she dies, right?)

And so onward, to Long Island University (which has a prominent link to the School of Pharmacy right there on the home page). Exactly where at LIU they are is not stated, but she meets with Mimi Pezzuto, a pharmacy historian at LIU Brooklyn, so they might be there. Pezzuto tells Grey that she has found some material about Izzie in the archives and hands her a small booklet (this particular copy was digitized from the University of Michigan's collection).

Grey thinks it looks kind of like a yearbook, and Pezzuto agrees that's pretty accurate. On page 29 is a list of students who graduated on May 13, 1915:

And there's Izzie! Now that she knows he officially graduated (when he was 24 years old), Grey wonders exactly what it took to do so. Pezzuto points her to another page with information about the system of instruction, and Grey reads the paragraph about the Junior Course:

The booklet also has several photographs, which the women do not discuss (at least not on air). I wonder if Izzie is one of the people in the graduating class shown on the page between 28 and 29:

Grey is impressed. Izzie was very young and didn't speak English before he arrived in the U.S. Here he had to learn English as a second language (or likely third or fourth language, since he already spoke Yiddish, probably some Russian, and maybe some Hebrew also), and then learn Latin for his pharmacy classes. He was taking hard science classes. Obviously he had drive and wanted a better life, and clearly he was very smart.

Grey asks how much tuition cost, and Pezzuto says it was $100/year (although page 13 in the booklet indicates it was $105 for a senior, and I'm guessing Izzie was a senior since he graduated). To be admitted he would have needed a letter verifying he had "good moral rectitude" from a rabbi or possibly a drugstore owner, if he were working for someone. A pharmacist deals with poisons and narcotics so has to be someone who can be trusted with those materials. Grey wonders how being a pharmacist now compares to what it was like then. Pezzuto says that in the early 1900's about 95% of pharmacists owned their own stores and there was a store on almost every corner.

The narrator interrupts at this point to tell us that in the early 1900's, the pharmacist was at the center of the immigrant community. He was an educated health professional and could dispense medical advice and medications. Many pharmacists were community leaders and mentors.

Going back to Grey and Pezzuto, the latter adds that becoming a pharmacist was a move to a professional occupation, which would be an honor for Izzie and for his family. It was prestigious and a move up from working as a printer. But why would Izzie have made such a move? In the early 1900's, Jews were not hired for many jobs. Some advertisements would actually say "Jews need not apply." Many immigrants chose to go into professions and work for themselves, where they would be less affected by anti-Semitism and could rely on themselves. (And suddenly I understood why so many of my cousins became pharmacists.)

Grey asks what happened to Izzie after his graduation. Pezzuto admits she has one more document and brings out a copy of Izzie's World War I draft registration (which has nothing to do with the history of pharmacy or the Brooklyn College of Pharmacy, but I guess they needed some way to segue to the next talking head).

Pezzuto explains that registration for the draft was mandatory for men between 21 and 31 years old. Izzie's card shows that he lived at 107 Bristol Street (the same address as the 1937 photograph) and was employed by himself, and his store store was at 207 Sutter. Oh, and he claimed exemption from the draft as "support conscientious objector" (which is incredibly difficult to read, and Grey had to ask Pezzuto what it said). Grey's reaction? "Oh, my left roots."

After Grey asks, Pezzuto says it would be very unusual to be a conscientious objector in 1917. She doesn't know more about the subject but can send Grey to a Jewish historian, who will be able to give her more information.

Leaving Pezzuto, Grey is surprised by how different Izzie seems now from what she had seen. She never saw him in his element (wasn't the pharmacy his element?) or his best light. She is impressed at his ability to make a better life. He was ambitious, smart, and a self-made person. And she is almost blown away by the fact that Izzie rejected the draft and was a conscientious objector.

I could not identify Grey's next stop, but she meets Tony Michels, an American Jewish historian from the University of Wisconsin at Madison and asks him what being a conscientious objector encompasses. In response he hands her a copy of the List of Enrolled Voters for the 23rd Administrative District of the Borough of Brooklyn for the period ending December 31, 1917. She pages through to the 16th Election District and finds Israel Brower listed as a Socialist. (Unfortunately, only 1919 is available online for Brooklyn, and I can't find Izzie's name in it.) The Socialist Party was opposed to World War I because it believed it to be instigated by capitalists and imperialist countries that considered the everyday man to be dispensible cannon fodder. So Izzie, as a good Socialist, would be opposed to the war and therefore registered as a conscientious objector.

Being a conscientious objector would have definitely been a minority position at the time. It could be risky because it was not a popular stance. Someone could possibly have been arrested or fired. Perhaps worse, you might be perceived as unamerican, not good for an immigrant fairly recently arrived in the country. As newcomers, immigrants were particularly vulnerable to accusations. Grey makes the obvious association with today's news. So to put yourself out there as a conscientious objector definitely took courage. You were making a statement.

But where would Izzie have learned about these Socialist ideas? Michels says he probably would have had some strong leanings already and likely was exposed to the ideas in Podolia, where there was already a burgeoning workers union movement among Jews and others. (Hey, my great-grandfather was from Podolia, and he was a Socialist, too!)

The narrator pops in for another short commentary. From 1791 on most Jews in the Russian Empire were confined to living in the Pale of Settlement and were barred from many jobs and educational opportunities. During the 1905 Russian Revolution, some groups, many Jews among them, fought for working class equality. Afterward, Jews suffered from increased anti-Semitism. To escape these unpleasant circumstances, many Jews took the risk and left Russia for the new World.

Michels has another document that may shed some light on Izzie. It is the April 1935 issue of Health and Hygiene, the medical magazine of the American Community Party. (Michels does not mention that it is actually the very first issue of the magazine.) Grey looks at him rather askance — seriously, Izzie was a sympathizer of the Community Party? Michels points out that in 1935 the Community Party was not what she thinks; it even supported FDR. He tells her to "browse around" the issue.

Grey flips through some pages. There are articles on children's diseases and the dangers of drugs and beauty aids. Overall, it seems to be pretty progressive in its views and not out of line with some of today's perspectives. But what does it have to do with Izzie?

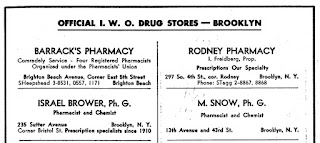

Michels points her to the inside back cover, which has a list of official IWO drugstores in Brooklyn. Michel says that the idea of the magazine was that health care was a right. IWO stands for International Workers Order, which was a self-help cooperative. Members paid dues for insurance and discounted rates. And when Grey looks down the page (oh, of course she didn't do that already), she finds a listing for Izzie's pharmacy. (And none of us was expecting that either, right?)

By signing up as an official IWO drugstore, Izzie showed an interest in serving his community. He also committed to adhering to the IWO standards. Therefore they were recommending him and saying that he could be trusted. Grey sees how Izzie's belief in Socialism meant that he believed in social justice and giving back.

But there's something else that Grey still wants to find out. She tells Michels that she's learned a lot about Izzie but that there are still a few holes in the journey. Izzie's mother never came to this country (which she doesn't actually know, at least based on what we've seen during the program). Michels says he has a research document that "just arrived yesterday" from the state archive in Vinnitsa, Ukraine. That archive has documents relating to Yampol, Podolia, where the Brower family came from.

The document is, of course, in Russian, but Michels gives Grey a translation. She begins to read it and says sadly, "I thought that might have happened." (And we all know what's coming.)

No 8 Shayndl, a wife of Shulim Browerman from Dzygovka, died 27th of August 1897 in Yampol at the age of 35 from childbirth

Grey is in tears. Izzie was 6 years old when his mother died. The children came to the U.S. in 1907. Who took care of them in between? Michels admits there is no information about that. (But since we weren't shown when Solomon arrived, there may not have been a big gap of years.)

Grey is still devastated. Her mother didn't know Shayndl's name. How could she not know the name of her own father's mother? Michels gently explains that the immigration experience caused a rupture in continuity, and family information was often lost or not passed down. If memories of the old country were not pleasant, immigrants had no desire to reminisce about them.

Grey looks at this as an explanation of Izzie's desire to go into medicine and helping people. He grew up in insecure circumstances (which we don't actually know), political unrest, and anti-Semitism and therefore wanted something more stable.

Before leaving, Grey thanks Michels and tells him how much she appreciates his patience and that he explained things so well.